Camera traps unable to determine whether plasticine models of caterpillars reliably measure bird predation

Abstract

Sampling methods that are both scientifically rigorous and ethical are cornerstones of any experimental biological research. Since its introduction 30 years ago, the method of using plasticine prey to quantify predation pressure has become increasingly popular in biology. However, recent studies have questioned the accuracy of the method, suggesting that misinterpretation of predator bite marks and the artificiality of the models may bias the results. Yet, bias per se might not be a methodological issue as soon as its statistical distribution in the samples is even, quantifiable, and thus correctable in quantitative analyses. In this study, we focus on avian predation of lepidopteran larvae models, which is one of the most extensively studied predator-prey interactions across diverse ecosystems worldwide. We compared bird predation on plasticine caterpillar models to that on dead caterpillars of similar size and color, using camera traps to assess actual predation events and to evaluate observer accuracy in identifying predation marks a posteriori. The question of whether plasticine models reliably measure insectivorous bird predation remained unanswered, for two reasons: (1) even the evaluation of experienced observers in the posterior assessment of predation marks on plasticine models was subjective to some extent, and (2) camera traps failed to reflect predation rates as assessed by observers, partly because they could only record evidence of bird presence rather than actual predation events. Camera traps detected more evidence of bird presence than predation clues on plasticine models, suggesting that fake prey may underestimate the foraging activity of avian insectivores. The evaluation of avian predation on real caterpillar corpses was probably also compromised by losses to other predators, likely ants. Given the uncertainties and limitations revealed by this study, and in the current absence of more effective monitoring methods, it remains simpler, more cost-effective, ethical, and reliable to keep using plasticine models to assess avian predation. However, it is important to continue developing improved monitoring technologies to better evaluate and refine these methods in order to advance research in this field.

Check out the full text

Schillé, L., Plat, N., Barbaro, L., Jactel, H., Raspail, F., Rivoal, J.

B., ... & Mrazova, A. (2025). Camera traps unable to determine

whether plasticine models of caterpillars reliably measure bird

predation. PloS one, 20(3), e0308431.

Fig 1. Photographs of the experimental design in the field. Red arrows point toward the camera traps. Blue and yellow arrows point toward five plasticine models (a) and three corpses (b), respectively. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0308431.g001

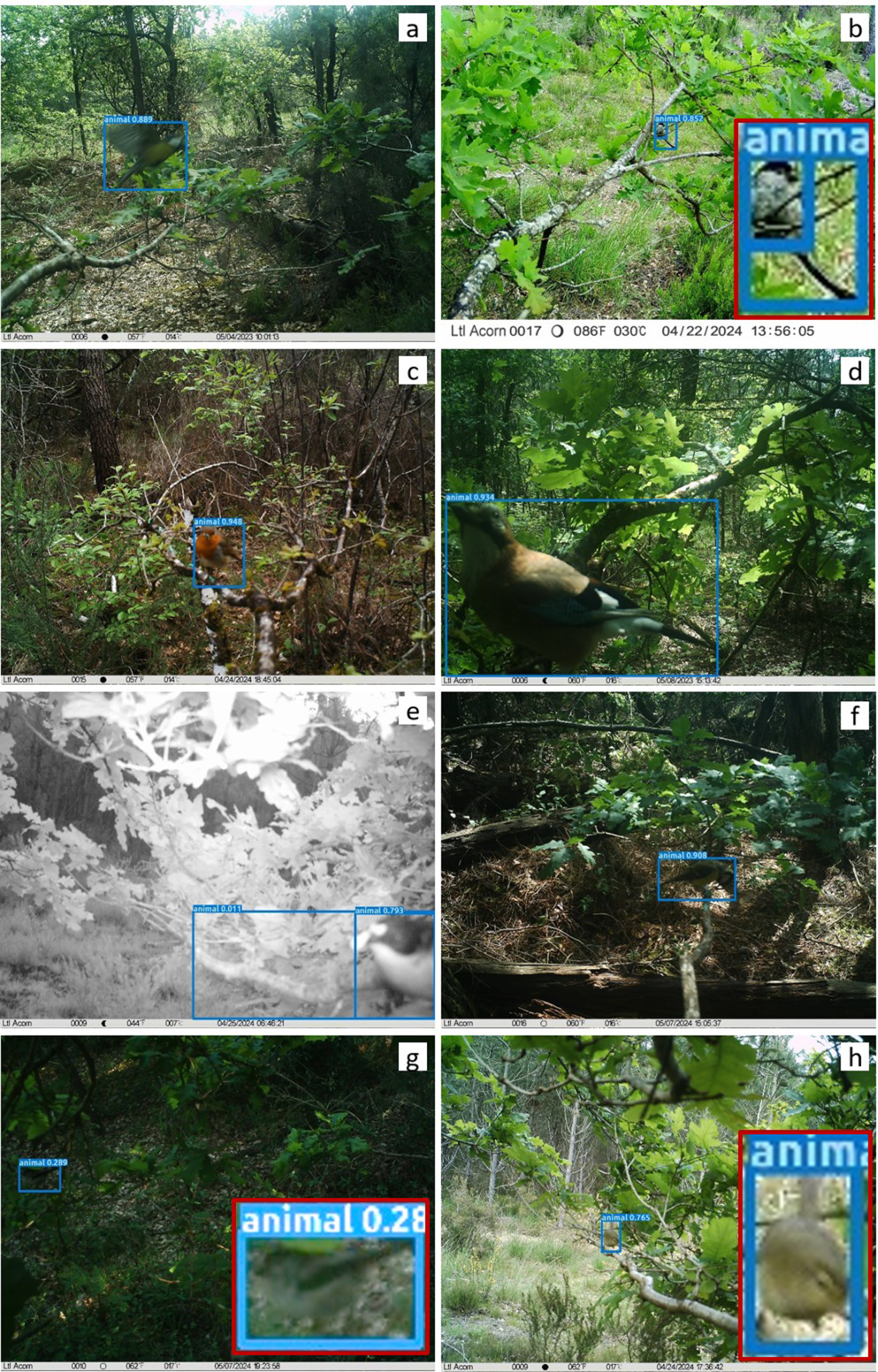

Fig 2. Camera trap photographs of birds taken in various contexts. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0308431.g002

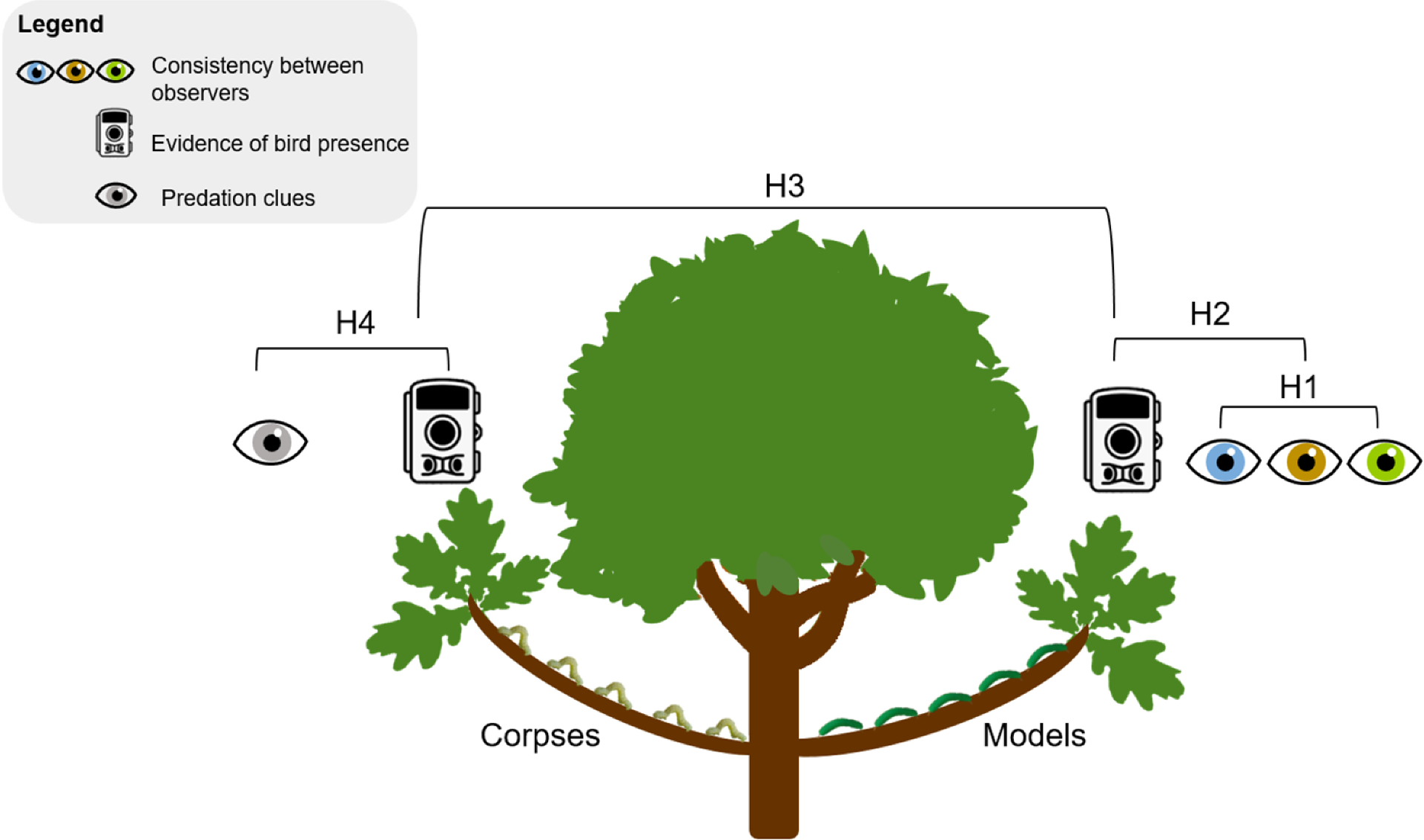

Fig 3. The experimental design testing the four hypotheses. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0308431.g00

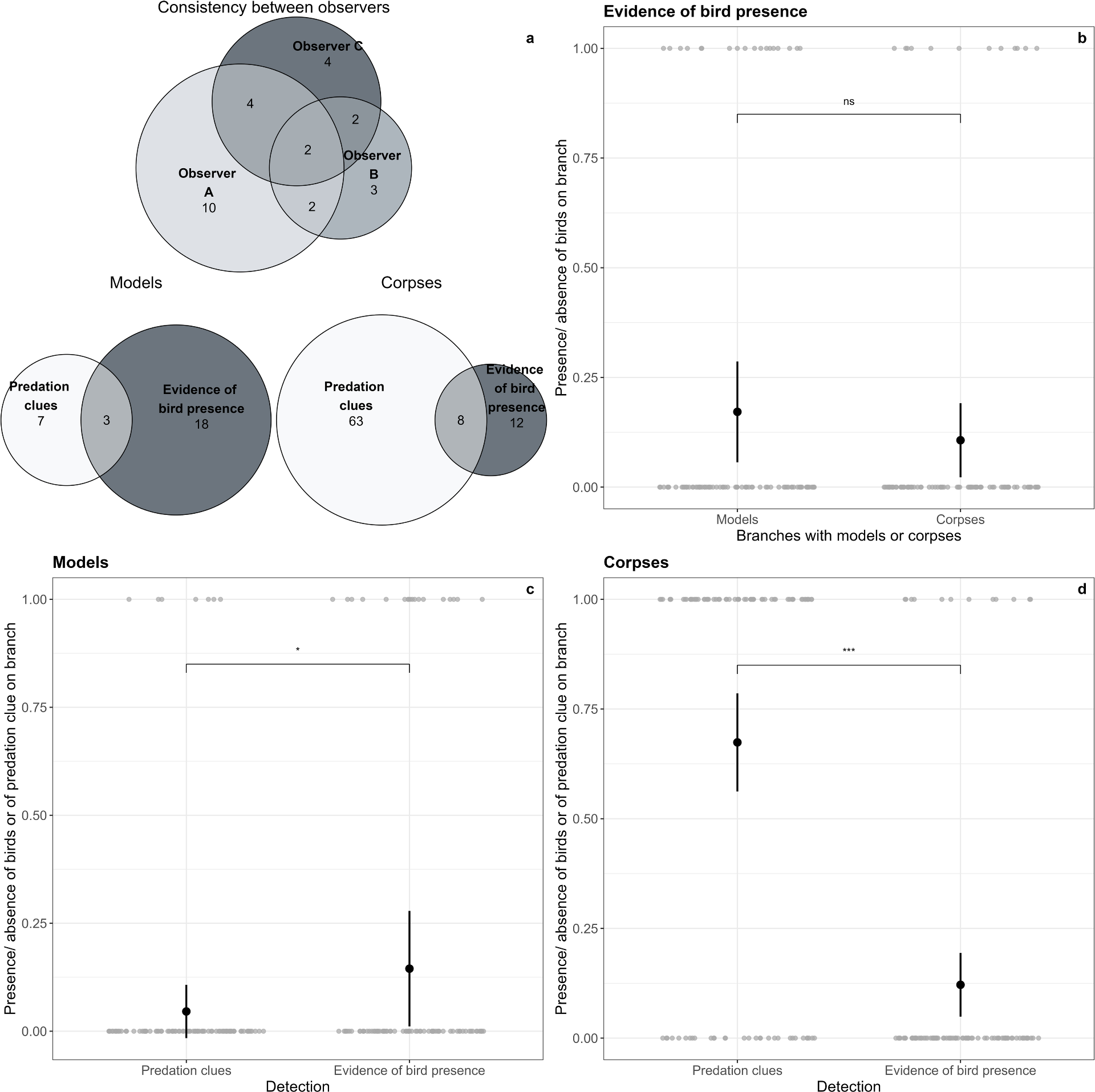

Fig 4. Main results of the study. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0308431.g00

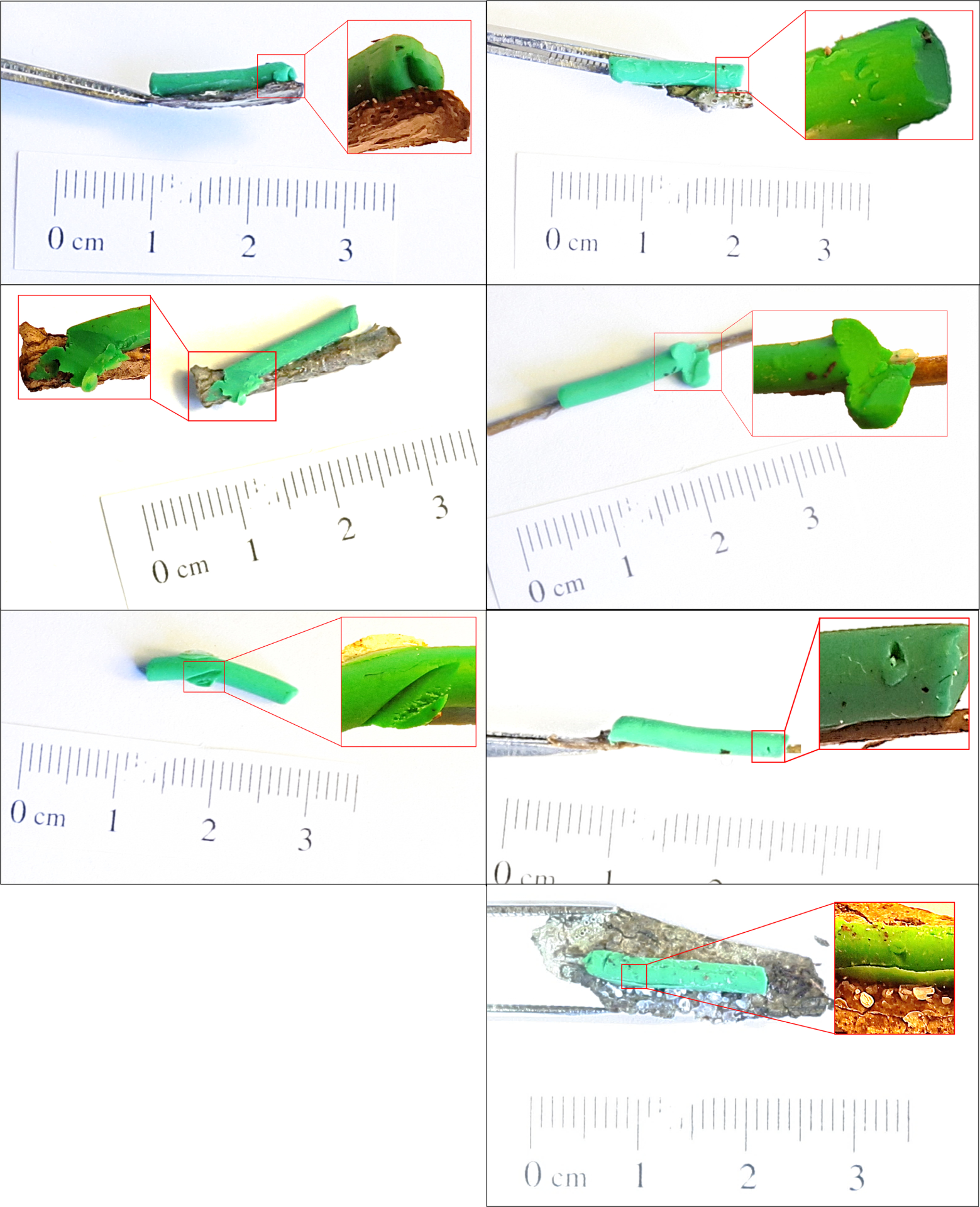

Fig 5. Photographs with mark details. Seven caterpillars that observers considered to have bird predation clues. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0308431.g00

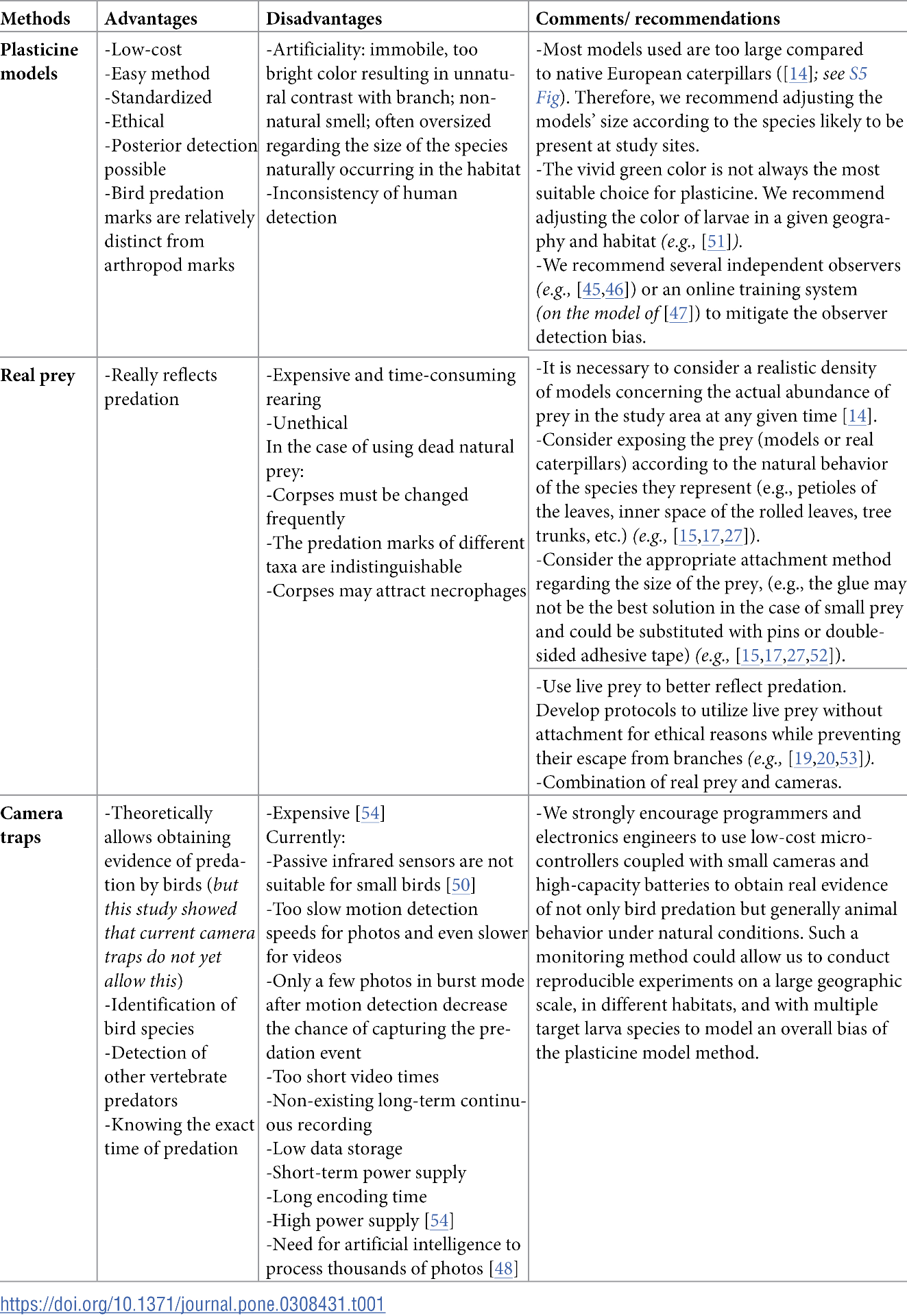

Table 1. Advantages, disadvantages, comments, and recommendations for the three possible methods of assessing bird predation: plasticine models, real prey, and cameras in their actual state of development. Note that cameras must be used in combination with one of the other two methods. If a cell in the third column spans two rows in the first column labeled 'Methods,' it applies to both methods. Literature references supporting our arguments are marked in italics. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0308431.t001